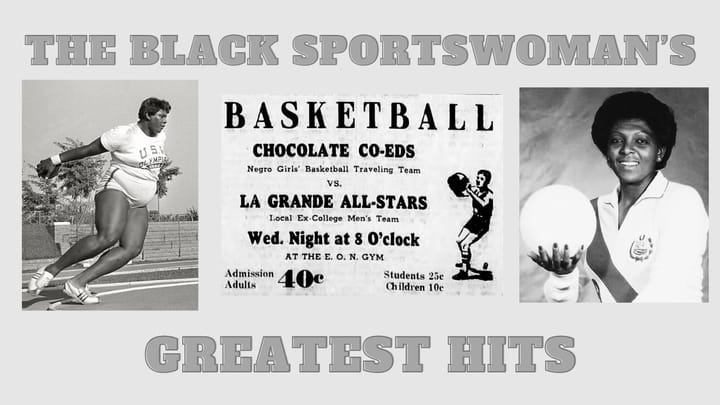

How Tuskegee invested early in competitive sports for Black women

The Tuskegee Institute was one of the first college athletics programs to invest in competitive sports for Black women.

The Tuskegee Institute was one of the first college athletics programs to invest in competitive sports for Black women.

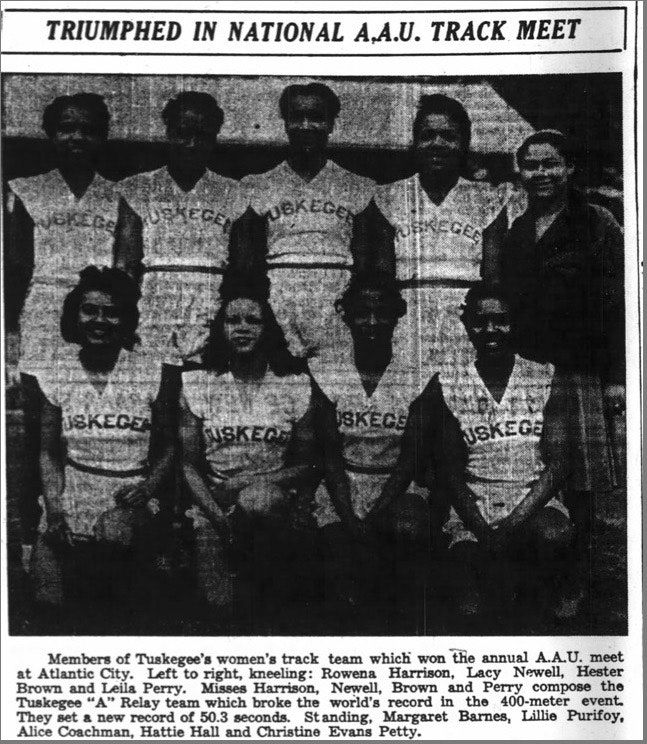

The Tigerettes began competing early in the 20th century, in basketball, tennis, golf and track and field. And in track and field particularly, Tuskegee went on to dominate the nation, winning national AAU track & field titles and setting records, from the late 1930s to the early 1950s.

Tuskegee also laid the foundation, by developing what can be called The Tuskegee Model, for competitive programs that would eventually become internationally accomplished, known and respected.

How the program was built

In 1923, the Abbotts arrived at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Officially, Cleve (1894-1955) was brought in to serve as athletic director and Jessie S. (1897-1982) worked for Margaret Murray Washington, Jennie B. Moton, and Dr. George Washington Carver. Together, they built up the school’s athletic department and created multiple programs and organizations: Southern Tennis Association, Southern Basketball Conference, Tuskegee Golf Tournament and Tuskegee Relays.

There are photos of Tuskegee women’s basketball teams from the early 1920s, but the Tuskegee Relays, which is described as both “carnival and sporting event,” started in 1927 and by 1929, women started to compete. By 1933, the school developed full women’s track and field events.

“Some of the Tuskegee people didn’t think too much of (women competing),” Jessie S. Abbott told A. Lillian Thompson in a 1977 interview. “And the boy athletes, they tried to discourage the girls from participating in sports. They competed anyway and (Cleve) kept going.”

As the Tuskegee track and field program was growing, other schools around the country were cancelling competitive athletics for women due to pushback. The reasons varied depending on the school.

“Since “decent” white women did not participate in such a masculine, competitive sport, African American women’s participation and success in track and field reinforced racial and sexual stereotypes long held by white society,” writes Jennifer H. Lansbury in her book A Spectacular Leap: Black Women Athletes in Twentieth-Century America. “In particular, the myth that African American women were better suited for hard labor, either within or outside the confines of slavery, helped explain both their suitability for and superiority in rigorous sport.”

But what the Abbotts built, using “The Tuskegee Model” in track and field, led to national dominance for their program, and eventually others.

The process started with the Relays, which were a big deal. The United States Olympic Committee even designated the 1936 meet an Olympic trial semifinal. The Relays eventually became a way for coaches to scout younger athletes, to attend Tuskegee or another school.

This is how Cleve Abbott took notice of Alice Coachman, who would become the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal, which happened in 1948.

Step 1: Abbott took notice of young talent at the Relays, where students participated while in high school.

Step 2: Abbott invited the young talent to Tuskegee’s summer program, where college athletes were training for AAU national championships. This allowed the prospect to see everything the Tigerettes did up close.

Step 3: When it came down to choosing a college, the top athletes wanted to be at Tuskegee, after all, they got a behind the scenes access look at success and domination during the previous summer.

Optional Step 4: Abbott helped the students attend the school via work study, a workaround for athletic scholarships. The top athletes, like Coachman, could transfer to Tuskegee to finish high school.

“At Tuskegee, Coachman discovered a community that encouraged and appreciated her talents, a coach willing to defy traditional race and gender stereotypes to develop his athletes’ potential and teammates who shared her competitive nature and love of the sport,” Lansbury wrote.

While Abbott brought in the talent, Christine Evans Petty cultivated it. Petty coached the team, while teaching physical education at the school, from 1936-1942. Abbott remained involved, but Lansbury writes that Petty never wanted the team to get cocky and described the coach as “petite and tough.”

The team became dominant by the mid 1930s. The Tigerettes were known around the country and they became the first all-black women’s team to compete nationally.

Chicago’s Tidye Pickett was the first Black American woman to compete for the U.S. in the Olympics in 1936 in the 80-meter dash. And Coachman won gold in 1948. But in 1940 and 1944, an athlete like Tuskegee’s Lula Hymes, could have been the first to win gold had the games not been cancelled, writes Liam Boylan-Pett in Løpe Magazine.

The previously mentioned step-by-step recruiting format was also followed by Ed Temple at Tennessee State, who cultivated athletes like Wyomia Tyus, the first person to win back-to-back Olympic golds in the 100-meter dash. Tennessee State’s Wilma Rudolph’s first major track event was the Tuskegee Relays.

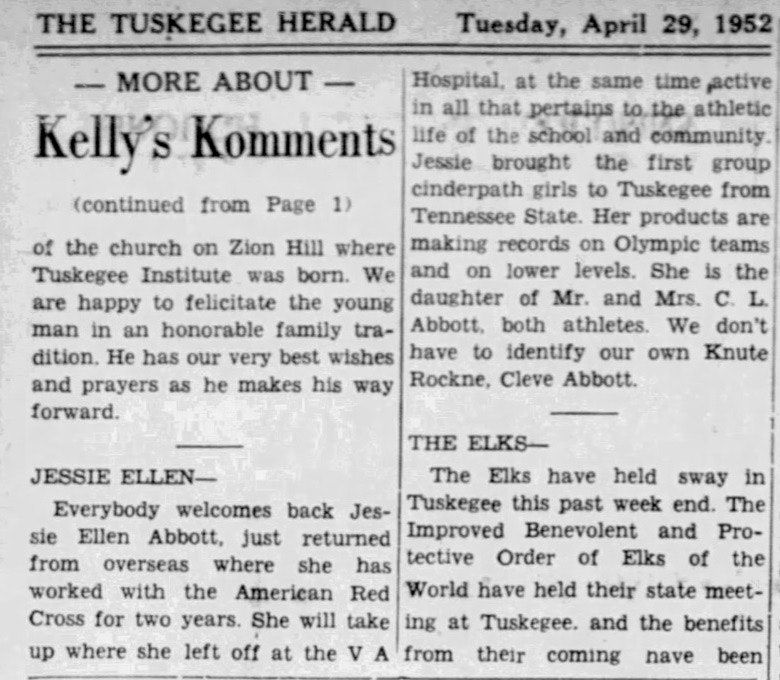

The connection between the school isn’t random. Cleve and Jessie S.’s daughter, Jessie Ellen, who competed for Tuskegee. She was also the first coach of the Tennessee State women’s track and field team in 1943. She brought the team, eventually called the Tigerbelles, to compete at Tuskegee, following the model created by her father.

“Abbott brought with (her) a commitment to excellence gained at Tuskegee Institute, home to the first nationally dominant African American track and field program,” said Carroll Van West. “Abbott’s Tuskegee model shaped what happened at Tennessee State for the next generation of sport.”

The internationally known Tennessee State Tigerbelles dominated the country and Olympics in the 1950s and 60s. Ed Temple even served as the Olympic women’s track and field coach. The Tuskegee Model is not just a step by step recruiting process Abbott developed, but it’s also a model of investing in Black women.

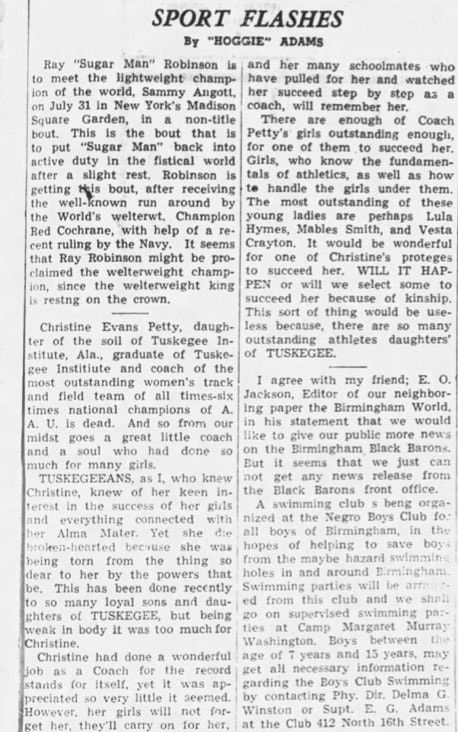

Christine Evans Petty died on July 3, 1942, two days before Tuskegee won its sixth-straight national title.

Following her death, Hoggie Adams wrote in the Weekly Review, “And so from our midst goes a great little coach and a soul who had done so much for many girls.

“Christine had done a wonderful job as a coach for the record stands for itself, yet it was appreciated so very little it seems.”

After Petty’s death, Cleve Abbott began coaching the team again. Abbott died in 1955 in Tuskegee, Alabama after an illness.

The New York Age wrote following Abbott’s death, “In 1923 the late Booker Washington summoned to his beloved Tuskegee a talented and dynamic young man who was to become one of the outstanding figures of his times.”

The obituary’s headline was “A Champion’s Champ. “Abbott’s place in the hall of sports fame has been assured for many years. But it should be said of him also that he belonged to that small corps of selfless, dedicated men who give their life’s work - and indeed their very lives- for others.”

Comments ()